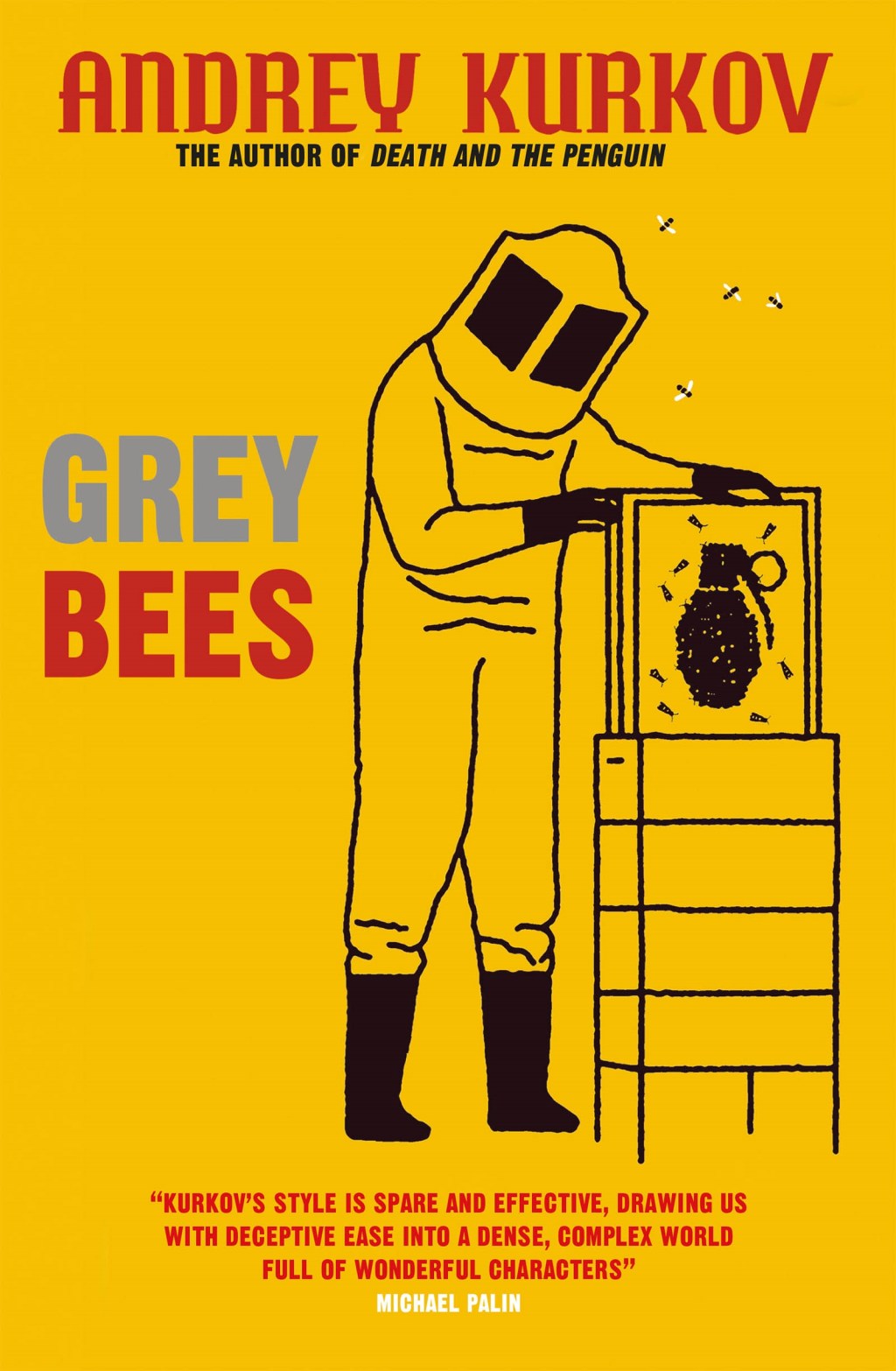

Grey Bees: Foreword by Andrey Kurkov

Seven years ago, in 2013, Vladimir Putin’s failed attempt to tear Ukraine away from Europe and fold it into his “family of fraternal peoples” – that is, into his revived version of the Soviet Union – ended in revolution. As a result of the popular uprising that came to be called “Euromaidan”, the nation’s pro-Russian political élites, led by the then-president Viktor Yanukovych, were forced to flee Kyiv for Moscow. In 2014, as power passed into the hands of pro-European forces, Russia managed to capture the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea and to send officers, volunteers, and activists to Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, Odessa and other cities in the east and south of the country, in order to foment anti-Kyiv revolts. Thus began a war that Russia does not wish to end, and which it regularly refuels with military personnel and thousands of tons of equipment and ammunition. Putin’s calculation is simple: a Ukraine with a permanent war in its eastern region will never be fully welcomed by Europe or the rest of the world.

And indeed, the world has largely forgotten about Ukraine and its war, as it always forgets about “quiet”, unfinished conflicts. The front line between Ukrainian troops and pro-Russian separatists in the breakaway “people’s republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk in the east is about 450 kilometres long. And the “grey zone” between these two sides is of the same length, but its width ranges from several hundred metres to several kilometres, depending on the intensity of hostilities and the landscape along any given stretch. Most of the inhabitants of the villages and towns in the grey zone left at the very start of the conflict, abandoning their flats and houses, their orchards and farms. Some fled to Russia, others moved to the peaceful part of Ukraine, and others still joined the separatists. But here and there, a few stubborn residents refused to budge. They stayed where they were, in the midst of a war, listen-ing to the whistle of shells overhead and occasionally sweeping shrapnel from their yards. Some of these holdouts have already been killed, but others have endured in this new, strange and harsh reality, in villages that were once densely populated but are now devoid of life, where all the shops, post offices and police stations have been shuttered. No-one knows exactly how many people remain in the grey zone, inside the war. Their only visitors are Ukrainian soldiers and militant separatists, who enter either in search of the enemy, or simply out of curiosity – to check whether anyone’s still alive. And the locals, whose chief aim is to survive, treat both sides with the highest degree of diplomacy and humble bonhomie.

![]()

Listen from 21.00 to a dispatch from Ukraine from Andrey Kurkov himself.

Since the winter of 2015, less than a year after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the start of the conflict, I have taken three journeys through Donbas, the eastern region that contains Donetsk, Luhansk and the grey zone. There I witnessed the population’s fear of war and possible death gradually transform into apathy. I saw war becoming the norm, saw people trying to ignore it, learning to live with it as if it were a rowdy, drunken neighbour. This all made such a deep impression on me that I decided to write a novel. It would focus not on military operations and heroic soldiers, but on ordinary people whom the war had failed to force from their homes.

These people have certain things in common. They try to remain inconspicuous, almost faceless, partly in order to remain un-noticed by the war. But they have always been that way in Donbas, a land of coalmines and metallurgical plants. In Soviet times, these people were proud to play an inconspicuous part in the “great industrial whole”. The Russians even came up with a special designation for them, “the people of Donbas”, as if they were the children of mines and slag heaps, without ethnic roots.

The protagonist of my book, Sergeyich – a disabled pensioner and devoted beekeeper – is one of these “people of Donbas”. The winds of fate carry him down to Crimea, where he hopes to arrange a proper holiday for his bees. Sergeyich’s southern sojourn, how-ever, proves to be an ordeal. Try as he might, Sergeyich cannot remain entirely neutral as he observes the constant oppression of the Crimean Tatars by the new authorities. His sympathy for these Muslim people arouses the suspicion of the Russian security ser-vice – the notorious F.S.B. – and, even more alarmingly, endangers his beloved bees.

My family and I last visited Crimea in January 2014. Even before the annexation, Russian flags fluttered everywhere in Sevastopol. The second half of this novel is, in some ways, my personal farewell to the Crimea that may never exist again.

Nor do I know when I will next return to eastern Ukraine, or when the conflict will end. But I sincerely hope the war leaves the residents of the grey zone alone – that it goes away, and that the honey made by the bees of Donbas loses its bitter aftertaste of gunpowder.

Grey Bees is translated from the Russian by Boris Dralyuk